The world is in a changing era. And Europe is discovering — with a growing sense of urgency — the need to achieve greater autonomy. The armed assault launched by Russia on its eastern flank and growing doubts about the credibility of Washington’s promise of military protection have produced an abrupt change in mentality. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz crystallized this idea by stating that Europe needs to be independent from the United States, a concept with more political force than the generic concept of strategic autonomy.

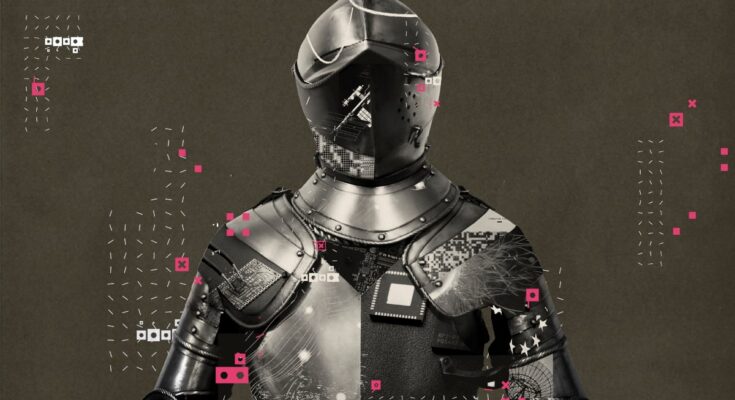

The main focus of attention is the defense sector. However, any project to stop being dependent or subjugated in the contemporary world requires achieving a high level of capability in key technologies, such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing and space technology.

An episode from last March starkly illustrates how crucial it is to have certain technological capabilities. Elon Musk took it upon himself to emphasize — via a message posted on the social media platform X — that Starlink, his satellite-based internet service provider, is “the backbone of the Ukrainian army. Their entire front line would collapse if I turned it off,” the tycoon noted, in a subtly threatening manner. This was especially concerning when considering other messages he posted around that time, in which he expressed frustration with Ukraine’s leadership.

The problem is that, without Starlink, Russia could indeed inhibit conventional connection systems. And Europe has no alternative to the service offered by Musk’s company. In this case, it depends not on an allied government, but directly on a single private foreign company. Hence, even having large arsenals wouldn’t be enough to guarantee security. There would need to be key technological conditions for the efficient use of those military resources.

The reality is that Europe lags behind the U.S. and China in key technological areas, which exposes it to dangerous dependencies. A recent report published by Harvard University’s Belfer Center — using complex comparative analysis — confirms that the great Western power on the other side of the Atlantic retains its lead in the five crucial sectors studied: artificial intelligence, biotechnology, semiconductors, space technology and quantum technology. China is in second place, with particular strength in biotechnology and quantum technology, in some cases closing the gap with — and even showing signs of overtaking — the US. European countries, meanwhile, are far behind.

When the EU is considered as a whole, Harvard estimates that the bloc’s capabilities are equivalent to half of those of the U.S. and two-thirds of those of China. Most glaringly, Europe is lagging in the semiconductor and space technology sectors, allowing Musk to make such a chilling observation.

U.S. dominance is largely due to its unique ecosystem. This consists of a deep, profitable and flexible capital market that provides oxygen to businesses; a track record of attracting foreign talent; as well as a business culture that’s highly conducive to innovation. China’s progress is largely due to the regime’s strong will to advance along this path, coupled with its executive capacity, the enormous scale of its market and its vast human resources. Europe, meanwhile, lacks both the depth of capital markets and strong, unified political will.

The fragmentation that still plagues the common market in the financial sector is a key obstacle on Europe’s path toward technological rearmament. In a report on the common market, former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta pointed out how this fragmentation reduces the profitability and efficiency of the European market to the point that, each year, some €300 billion of European savings ($350 billion) flow into the U.S. market, subtracting resources on one side of the Atlantic and fueling business projects on the other, thanks to readily-available U.S. financing. This is a crucial issue, because while the public sector can foster initiatives and support projects, true progress won’t be possible in Europe without effective private financing.

This past March, the European Commission launched a package of initiatives to advance the completion of a single financial market. However, the road ahead looks arduous, especially considering all the resistance that has so far impeded greater cohesion.

Another key factor in Europe’s race for technological rearmament is its acute dependence on strategic raw materials — such as lithium, cobalt and rare earth elements (REEs) — that are essential for developments in the sector. In this area, China holds a worrying position of dominance that can be used as a tool to either pressure or blackmail other parties.

In 2024, the EU approved a law aimed at increasing the extraction, processing and recycling capacities of these types of raw materials. Brussels periodically monitors the level of dependence on certain key minerals. The idea is to increase resilience, but in this regard, too, the path seems difficult, given China’s dominance, as well as the social rejection of mining and refining activities in Europe.

The EU has launched sector-specific actions to catch up. Perhaps the most notable is the European Chips Act, which came into force in 2023: the legislation seeks to boost the design and manufacturing capabilities of advanced semiconductors across Europe. These microprocessors are essential in any strategic technological endeavor. The stated goal is to achieve a 20% global market share, up from the current 10%. However, experts point out that this is a difficult goal to achieve. A dire sign of this difficulty is Intel’s decision to postpone the launch of production plants in Germany and Poland, which were going to be symbols of the manufacturing renaissance in Europe.

The microchip issue also points to another area that must be addressed in the European technological drive. Several countries have been competing with each other, using promises of subsidies to attract the establishment of manufacturing plants in their territories. This calls into question the rules surrounding state aid: while this protocol is essential to ensure a balanced internal market, it can also represent a hindrance to global competition.

The enormous complexity of boosting technological competitiveness also affects trade policy. A key sector in this regard — one not considered in the Harvard report — is green technology. In recent years — especially in the automotive subsector — it’s clear that China has made giant strides in this regard. Faced with clear evidence of strong state support for the development of electric cars in China, last year, the EU decided to increase tariffs in this sector, so as to offset the imbalance caused by Beijing’s actions. This is meant to protect a development space for the local industry, in a sector that’s key for the future.

Regarding human capital — an essential driver of technological progress — Europe shows signs of trying to take advantage of the Trump administration’s hostility toward universities and foreigners. This is an opportunity to regain lost ground. Last May, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen presented the Choose Europe initiative in Paris, alongside French President Emmanuel Macron. This plan is intended to encourage researchers who want to leave (or are obliged to leave) Trump’s United States — or those who are forgoing future prospects there — to settle in European centers. The EU is also playing on the appeal of a free and democratic environment, compared to the repressive and authoritarian system in China.

Naturally, in parallel with community initiatives, EU member states are developing a plethora of national programs, just like other European states that don’t belong to the EU club. However, global technological competition is where you’ll find the strongest evidence that greater European integration is the only way to achieve competitiveness.

The Harvard report, for example, indicates that, if Europe has a degree of competitiveness in the quantum sector, this is due — in part — to the cohesion promoted by the Horizon Europe funding program. But fragmentation exists in many areas, and the path to overcoming it is fraught with obstacles. Yet, overcoming them is probably a necessary condition, not only to defend European competitiveness, but also to avoid becoming a vassal.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition